THE SIXTY EURO PROBLEM AND HOSPITALITY WORK AS A FEEDBACK

LOOP, REFRIGERATING THE WOOLLY MAMMOTH.

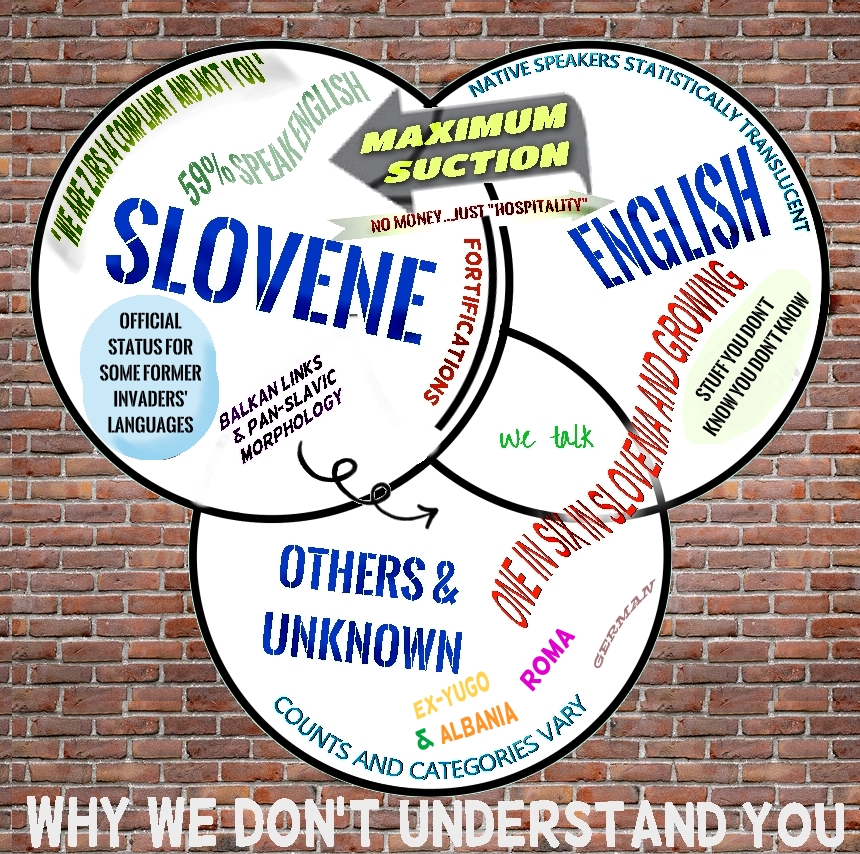

Slovenians believe they are being "hospitable" by denying their

language in the presence of foreigners and in one sense this is true.

But this is not the whole story.

This hospitality is the glacier, concealed inside of which sits a linguistic

mammoth, frozen and inaccessible.

Other considerations beset the teaching of Slovene to foreigners.

There may be worries about contaminating bloodlines. What are the implications

of foreign blood speaking Slovene?

Then there is their purpose in learning English in the first place: access to

wider markets and culture. Or "to be fancy".

And somewhere on the horizon, surely, is the problem of what the problem will

then be with these people, once the language problem has been swiftly dealt

with?

Yet speaking Slovene with foreigners at a gradually more proficient level does

nothing to solve the problem of escaping from Slovenia on the one hand, and

leaves them with at worst a loss (or back at zero if they charge).

After a softening-up preamble of pretending to be interested in you personally,

the conversation will move on to the actual knowledge the Slovenian hopes to

gain. Many are quickly disappointed if you are not a racist, chauvinist,

everything-phobic sports and car man with an interest in British royalty and a

tendency to believe alcohol is the answer to anything and everything.

Among the more interesting enquries: which are the posh English supermarkets I

should try to sell my wine to? Is it true there are a lot of gypsies in

Solihull? Such are the daily demands upon the free English representative and

his cornucopia of no-cost wisdom, sought by the Ptuj wannabes.

Would it be worth suffering this tedium even if it could be had in Slovene? Pivo

forms 33.33% of the pub Slovene lexicon.

By the third bar, the hospitable Slovenian will be unashamedly babbling the next

question like a machine gun as he tries to catch up on all the information which

has, apparently all his life, been unavailable or unconfirmed to him until this

foreigner's wondrous appearance - surely a sign of great good fortune to him,

like a bright star in the east.

No part of these evenings amounts to much that could be described as

educationally useful. Socialising is draining, as whatever banal information

Slovenians are determined not to miss is relentlesly sucked out of you.

The

informational flow is relentlessly unidirectional. The Complainant departing

these encounters appears uninjured, but feels as though he has just been peeled

alive.

Counter-enquiries will receive shrugs, don't-knows in return, or will often just

be ignored, as the foreigner is not allowed to lower his bit rate or run duplex.

You begin to suspect Slovene will turn out to be a spectacularly empty safe with

a particularly tricky lock. All social interaction must take place while losing

control of parts of your body and memory.

It's very hard to get answers out of them or propel the learning in a

straight line.

The would-be immersion-method student hoping for educationally-useful steps in

this environment is more likely to end up falling down some.

Remember however: the €60 being saved by Slovenians not speaking Slovene is only

a notional gain.

The real goal is to maximize each hour's gain from not speaking Slovene with as

much free English consultancy as the Slovenian can squeeze in, while succeeding

to a greater or lesser degree at dressing it up as pleasant chit chat. Whatever

topic is chosen, the Englishman is duty bound to know. The fact he probably does

just makes it worse for him.

The chance of picking up Slovene in these situations is limited to brief

encounters with untranslatable words, as he helps them struggle to explain what

they need the foreigner to tell them.

If the Anglophone knows the Slovene word, some confusion can be cleared, full

suction is resumed, and on in English they go.

Hospitality creates a problem with disloyalty to the Slovenian cause; there is a

problem, when communicating with the enemy, that the people in charge will not

know what is going on.

Most of Slovenia's interaction with foreign cultures is via the younger

generation.

Disloyalty may be suspected, and measures taken to rein in anyone getting

too frisky with their English or, in the worst horror imaginable for some, even

considering taking it up full time.

When it is pointed out they are being a teeny bit xenophobic, Slovenians

(unaware of ZJRS 13, 14 or 32, or the €9600 cost of the A1 course, or the courses for Albanian ladies only) will deny

they are demanding the Complainant speaks Slovene. They will invent excuses for

him. And for themselves.

When it is necessary to prove they are on side with racists in town, Slovenians

will compete at how angry they can be about demanding foreigners speak Slovene

(rabid youth, jealous coked-up sporty boys connected with the Town Smell, and

militaristic racists) while others will dutifully roll their eyes, and

tut-tut-isn't-he-ashamed (middle-class catholic racists).

When these two factions meet in the presence of €30's worth of alien per hour, sparks may fly.

Slovenia's solution to The Sixty Euro Problem - speak English and avoid the risk

of a notional double loss - melds easily with individual ambitions in the

employment world, in which ability at English may form a critical element.

So, empathising with them in a way they could never comprehend, besides the

€60/hour they are going to lose while slowly developing the English person's

Slovene, autochthons are motivated against improving foreigners' job prospects

generally, as this might conflict with or diminish their own, upset someone who

doesn't like foreigners who might have a job for them, or dilute the wages of

their fellow Slovene experts by encouraging and enabling alien competition in

the various EU money-grabbing projects which pass for economic activity in Ptuj,

for instance.

Consequently the sphere of Slovene employment is replete with people who know

Slovene, but very little else.

The people at the ZZZS to whom you are sent to find out why you cannot have

health insurance cannot explain, and tell you to bring a translator.

Their boss does not know how to copy and paste on a computer.

The people at the Council you need to talk to about lining sewers...have never

heard of lining sewers.

The people at LUP where Anglophones are sent by the ZRSZ to learn Slovene know

nothing about teaching Slovene to Anglophones.

With plumbers, building supplies, house renovations, interactions of every

category, it is as if everything I do, this is the first time anyone has ever

done this thing in Slovenia, ever.

And Slovenia's refusal to impart its language squats at the centre of this

wooden performance. And for wanting any of these in English as well, I should

pay double.

Slovenians are a little sad at the non-outcome nonetheless, but never suspect

they themselves might have any role to play in this static and unproductive

state of affairs.

Virtually all two million Slovenes are equally convinced this

Slovene-teaching is certainly not their job, must be someone else's, or perhaps

that teaching Slovene to English speakers is not a real job, or one that ought

to exist, at all.

The challenges facing Ljudska Univerza Ptuj in assembling an economically viable

cohort of English speaking pupils and competent English-speaking teachers of

Slovene are not my problem.

Not doing it is obviously more important to them

than receiving more than five times the minimum wage. In Ptuj.

If 51% of Europeans could hold a conversation in English in 2006 there must be

some other reason why English-speaking teaching of Slovene is retarded.

In the view of the Complainant, one reason is that Slovenians believe English

belongs to them, but that its native speakers do not properly belong among them,

but may be tolerated to the extent they are useful. Concerning language exchange

they are, however, too calculating to reciprocate.

This is what gives Slovenian hospitality its stilted, plastic feel. It is an

oily watery mess, doomed to forever mingle but never quite mix. Emulsification

is prevented by the discriminatory administrative practices, and the blatant

bigotry of the anti-foreign-ness laws ensure that foreigners and employment

slide off of each other in a frictionless embrace.

For according to this legal and administrative setup, what is the non-touristic

NSMT in Slovenia supposed to be doing, besides drinking, answering questions,

spending all his money, then leaving, or dying?

Any historical parallels? Even the Nazis only had a single national Jewish

Boycott Day, on 1 April 1933.

After years of intimidation, and Kristallnacht, on November 12 1938 the regime

issued a decree excluding Jews from economic life. Among other things, Jews were

forbidden to operate retail stores or carry on a trade. The law also forbade

Jews from selling goods or providing services at any kind of establishment. The

ZJRS forbids people who don't speak Slovene from doing the same.

Patriotic German anti-Zionist jews and anti-east-European-jew jews even sided

with Hitler in the early days. Nazi discrimination was not especially because of Yiddish,

which was ultimately more despised by jewish groups, from 18th century Europe to

20th century Palestine and Israel, and for being anything from an anti-Christian

plot to just low-class [65].

The Nazis sought broader rationales against their target group. But the effect

of the ZJRS and the discriminatory administrative practices are the same: make

life impractical for outsiders. The motive is to eliminate the economic power of

a supposed enemy within, over the nation. [23]

And it is true. The people in Ptuj are crazy jealous because I live in a house;

"The whole house?" they say.

Indeed the Slovenian media must feel they thrive on "jealonism" - a hybrid genre

of journalism and appeals to jealous-mindedness devoted to stories with the

format: "Look how fancy X's house/car is" - typically deployed against political

enemies. [70,73,74,75]

Language has been a rather neglected area of discrimination law. The de facto

outcome for the English speaking minority in Ptuj is as described, and would

appear likely to be fatal.

Slovenia's famous melancholy plays a role. But the challenges of finding Slovene

teachers from the aforementioned 51%, if real, do not diminish any rights under

the following treaties or, for what they are worth given the anti-English rules,

ZJRS 13 or Constitutional Article 14.

The ZRSZ has identified itself as a promoter of Slovene language education and

failed to coordinate effectively with the Ljudska Univerza Ptuj or other nearby

learning facilities, leaving the seeker of structured learning information on

the topic at the mercy of the general population. Every arm of officialdom is

meanwhile grateful something somewhere else is in charge of their language, in

order to prove it's not their fault.

The general population apparently have no idea how Slovene works, and a variety

of dodgy opinions on vocabulary and grammar, such as "nominative is the name of

a thing" i.e. imenovalnik = samostalnik. Which is wrong. 50% think h is not a

word [43]. Wrong. They are learning, but

unfortunately they are learning something about Slovene from me. They probably

won't remember any of it anyway.

But you can just talk to people eh? It'll be fine! Closer and closer, the

hospitality presses in, from all sides.

Emerging spittle-flecked and temporarily deaf from your first few hours of pub Slovene, you have learned everything about the language you are ever going to there.

In anti-educational environments ranging from interrogatory to hostile, at worst it can resemble seeking German lessons while under arrest by the Gestapo. And those three words are not enough. At best it is incredibly dull.

The mammoth sleeps on, occasionally asking

foreigners to remind it how long

they have been here, without learning Slovene. Hospitality does not want to

transition.